Search

[{{{type}}}] {{{reason}}}

{{/data.error.root_cause}}{{{_source.title}}} {{#_source.showPrice}} {{{_source.displayPrice}}} {{/_source.showPrice}}

{{#_source.showLink}} {{/_source.showLink}} {{#_source.showDate}}{{{_source.displayDate}}}

{{/_source.showDate}}{{{_source.description}}}

{{#_source.additionalInfo}}{{#_source.additionalFields}} {{#title}} {{{label}}}: {{{title}}} {{/title}} {{/_source.additionalFields}}

{{/_source.additionalInfo}}OMORI (PC)

OMORI

Developed By: OMOCAT

Published By: OMOCAT

Released: December 25th, 2020

Available On: Windows, MacOS

Genre: Psychological Horror, RPG

ESRB Rating: N/A

Number of Players: 1 offline

Price: $19.99

Terror.

Terror has come in many forms. In prehistoric times, it was the fear that you or your family could be consumed without a moment's notice. If you were living under Roman rule, you would live under constant fear of being deemed a political or religious enemy. During the Middle Ages, you may have been afraid of starving to death in the streets or dying in a futile war run by a tyrannical king to expand his dominion. In the early 20th century, we were horrified by the cruelty of war, and in the latter half we were paralyzed by the potential for a nuclear one. It is for this reason I find it rather humorous that the so-called "war on terror" marked a shift away from the terror I listed above. Sure, there was now the concern over terrorist attacks, but what used to define terror was no longer the common consensus entering the 21st century. Terror was searching for a new form. In the modern age, terror could come from the infinite fearmongering of news, or it could come from the endless stream of events shared instantaneously over social media. But terror for some today has been redefined into something much simpler and often considered "pathetic" to the terrors of old: the fear of being alone.

For me, OMORI perfectly exemplified this new terror. It is a social commentary on what can happen to an isolated mind. OMOCAT couldn't have possibly predicted it when she began development six years ago, but her game released at the tail-end of the largest isolation event in modern history. For nearly two years now, we've lived practically closed off from society and our friends. OMORI, similarly, follows the story of a young child named Sunny. We aren't explicitly told why until near the end of the game, but he's lived in isolation closed off from the entire world and his group of dear friends Kel, Aubrey, Hero, and Basil for five years. When you've lived for so long without basic human interaction, especially as a child, it can severely warp your perception of reality. Coupled with guilt, grief, and depression, it can destroy their hope and happiness. In the game, this takes the form of a floating white eye in an amalgamation of black mist known only as "SOMETHING".

Strong Points: Wonderful storytelling; great art; nice soundtrack

Weak Points: Battle system can be a bit tedious and repetitive

Moral Warnings: Themes of depression and suicide; comically graphic violence; PG light swearing; disturbing imagery involving hangings and stabbings

SOMETHING represents the same fear all children have felt—the belief that a creature would come to get you after you've turned the lights in the basement off or would gently open your closet doors before creeping out from the shadows. SOMETHING does not strike terror into those who play the game because it is horrific or alien, it weaves terror out of our childhood nightmares; a virtual recreation of the unpredictable hallucinations a child imagines even when in an otherwise safe scenario. It's SOMETHING we've all experienced. But OMORI is not only about SOMETHING. Just like when we were kids, it is about the moments when we know there is nothing. Children often feel safest in the day, and most afraid at night. A natural instinct for preservation when your fate could be decided by an attacker you never saw coming. It's why the game first begins in "WHITE SPACE", a bright-white illuminated room that repeats infinitely in all directions away from any danger. Upon first starting the game, all you're given are two simple sentences. "Welcome to white space. You've been living here for as long as you can remember."

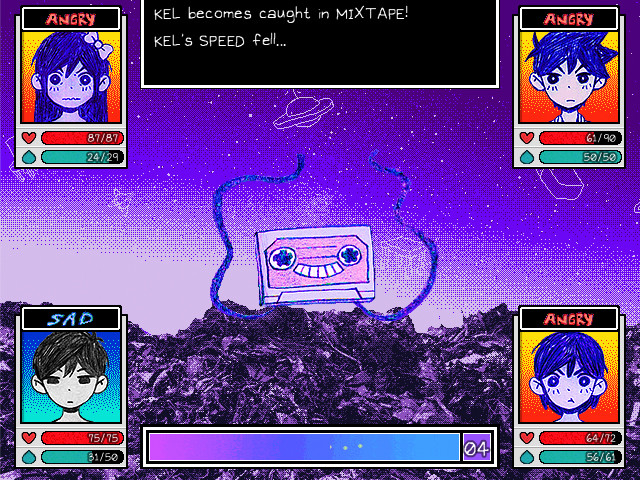

But what is OMORI as a game, you may be asking? "It isn't one of those anime book stories where you press the A button for fourteen hours is it?" I am proud to say that it is not one of those long anime book games. It's one of those very long turn-based RPG games. Today, we're spoiled for choice between our games. In the age of the NES, Genesis, and SNES, often times the best you could get were platformers, racers, beat 'em ups, space shooters, or those darn RPGs. Despite being a new entry in one of the longest-running genres of gaming (and entertainment as a whole), OMORI brings a lot to the table besides casting Fire for the entire game. Just like the story, OMORI's battle system is rooted in its three emotions: sadness, happiness, and anger. All of your members start the battle neutral, but enemy attacks or ally specials can change the mood of your party. In terms of what this actually means for the gameplay, we need to consult the emotion flow chart. You see, each emotion plays a part in a carefully balanced system of rock-paper-scissors. Angry characters do considerably more damage but take more as well; happy characters act faster and have a higher chance of hitting a crit but will miss more often; and while sad characters take less damage, their speed is lower and any damage taken will sap your juice, OMORI's equivalent of magic/power points for specials. Each emotion can also do more damage against a "weaker" emotion: happiness does more damage to anger, anger does more to sadness, and sadness does more to happiness. Each of the emotions also have stages where their stats are increased: a happy person can become ecstatic before becoming manic, a sad member can become depressed before becoming miserable, and an angry member can become enraged before becoming furious.

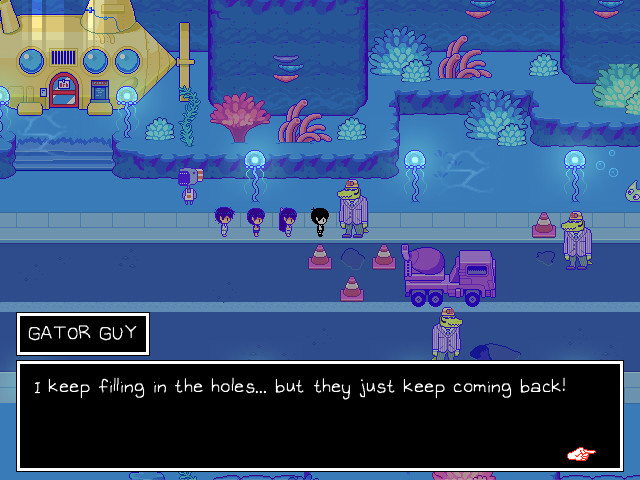

The purpose of OMORI is to unravel a story we haven't been read into, a tragic event that turned Sunny into a shut-in and fractured their friend group. The game takes place in two different sections, the real world of Faraway Town and the place of dreams called HEADSPACE. Every day and night before you go to sleep you can choose to adventure in Faraway, and once you go to bed you enter the world of HEADSPACE. The real world is harsh, abrasive, and combative to the dreamed events that occur in HEADSPACE. Although it's relatively obvious from the start, OMORI's incredibly cheery and kid-like exterior simply hides a darker and more sinister underbelly as you learn the true purpose of HEADSPACE. Like how as children we felt terrified in moments where we imagined SOMETHING sinister around us, OMORI attempts to lure you into a false sense of security. Its candy cane storytelling and psychedelic rough art truly makes you feel as if you've stepped into the world of a child's mind. It's completely nonsensical, overtly colorful and cheerful, and often will make you forget what you were so terrified of. As you explore a junkyard on a pink moon, a treasure hunt orchestrated by a dinosaur in the desert, or a shark's casino at the bottom of the sea, you will be caught off-guard when SOMETHING returns.

Higher is better

(10/10 is perfect)

Game Score - 88%

Gameplay - 16/20

Graphics - 9/10

Sound - 9/10

Stability - 5/5

Controls - 5/5

Morality Score - 91%

Violence - 4/10

Language - 7.5/10

Sexual Content - 10/10

Occult/Supernatural - 8/10

Cultural/Moral/Ethical - 10/10

OMORI scares the player just enough to make them wonder when the illusion of a pleasant dream world will finally break again, and when a new disturbing incarnation of SOMETHING will return. Like I said before, the rough pencil art of OMORI placed alongside its wonderful pixel art and animations appear as the idealistic drawings of a child's imagination. The incredibly bubbly, fast-paced, and random music does wonders to sell this point, as well as the moments of serenity provided by solemn piano pieces as you meet with your friends around picnic baskets. But as the game progresses and the music and art begin slowly disintegrating into the psychedelic ramblings of a shattered mind, the once calm and peaceful world is revealed to be a stand-in for a truth that no one wants to face.

I want to reiterate that OMORI is a fantastic game. I know I've focused so much on the story of OMORI rather than the gameplay or visuals or music, but that is because it is such a dense experience where every second has profound meaning and symbolism that only becomes more apparent as you progress. The only complaints I could bring up would be that the battle system can become repetitive, although that is more of a "me" issue with RPGs. I never struggled with difficulty, which is a surprise and perhaps a complaint. I very, very rarely purchased healing items but still managed to cheese most fights by abusing the emotion system. The default controls are also certainly an RPGMaker trait, as they can be cumbersome to remember and use. X is back, Z is confirm, the arrow keys move around, Q is the map, and so on. Thankfully, these are fully customizable, and a controller can be used as well. For this reason, I won't dock any points since rebindable controls always deserve praise. I, however, didn't know that and worked with them like a couple in marriage counseling. The resolution, however, is not customizable and instead locked to the same 4:3-esque ratio most RPGMaker games are stuck at. As a writer, I can give no higher praise to a fellow writer than saying I felt genuinely sympathetic and attached to a character and world they created; something I have been blessed to experience several times this year with games like Outer Wilds and Persona 5 Royal. One thing funny I've also noticed about horror games with a cult following is that their fandoms always try to make extremely happy/"wholesome" art about traumatic events that occur within them, and OMORI is no exception. So, just like how OMORI is a game about coping mechanisms, it has itself now become the thing that fans must create coping mechanisms for.

OMORI is largely a clean game. The dialogue has the occasional mild swear (h###, d###), but nothing worse than what you'd find in a PG film. To the best of my knowledge, there was no religious profanity. There is absolutely no nudity or sexual content in this game beyond some harmless flirting between a couple. Some cartoon violence is a part of the dream world, but more serious events transpire in the real world. My only concern would be, again, about the horror elements. Suicide and depression are two very big portions of the story. There are (sometimes graphic) depictions of hanged, stabbed, or decapitated bodies and haunting, ghostly figures. There is also very disturbing occult-like imagery, even if the story or world has no association with it, used to show how deep their delusions and nightmares can take them.

In summary, OMORI is a fantastic RPG that lasted me a hearty 40 hours, and that was only one playthrough. To get the most out of the game, you'd need to experience a second ending decided by some choices you make early on. The ludicrous art and experimental music, even if a bit rough around the edges, mesh perfectly with the narrative to create an unforgettable experience—one that I can absolutely recommend at its low $20 price tag. Underneath the alien presentation and sometimes Lovecraftian monsters and worlds, there is a genuinely good story about family, friends, and moving past loss together. I could never describe the game properly without spoiling the story, so give OMORI a try. I'm sure you'll find something to love, or SOMETHING to fear.